|

Modern Method |

|

|

|

Modern Method |

|

|

|

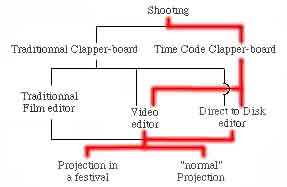

In the previous method, we've seen that most films were still shot without the use of time-code. There are several advantages to using time-code on a shooting, really speeding-up post-production, as we are about to see now... |

| The big change in regard to the two previous methods lies in the shooting |

Of course, you've read (!?!?!?) the section concerning what happens on a shooting, which will then make the following sound quite familiar :

Even though there are several possible variations, the main purpose of a shoot with time-code is to associate picture and sound with the same adresses from the start, to avoid waisting time resyncing later-on. Either an external generator (surch as Aaton's OriginC+, for example), either the audio recorder, can be the source of these adresses.

For sound, the time-code is generally recorded in LTC form on a dedicated track of the audio recorder.

For picture, there are several systems that manage to represent the adresses as a bar-code or dot matrix on the film :

To the right, the Arriflex bar-code.

To the left, the Aatoncode, with HH:MM:SS man-readable adress.

Even though, in theory, a clapperboard isn't neaded when shooting with time code, since both picture and sound media record the same adresses, most (if not all) film crews prefer the redundancy brought by a "man readable" time code also printed on film, by the means of a time-code clapperboard. I'm sure you've seen these several times already on TV : they're those clapperboards with the huge bright red display showing the 8 digits of the TC.

Some TC clapperboards have their own built-in generator, which the clapper/loader will frequently update by feeding it the output of the main TC generator of the shooting (see above), and then hoping the clapper's generator won't drift too much from that main generator.

Some TC clapperboards only feature the TC display (no built-in generator), and need to be permanently connected to the main TC generator. This can be done via a cable (which will inevitably tangle-up somewhere) or via a wireless transmission : a transmitter sends the main generator's TC, and a receiver is mounted on the clapperboard, plugged into its TC input. At least with this type of clapperboard, you don't have to worry about a possible drift between generators, since there is just one !

Now you've probably noticed, from all these "behind the scenes of a shooting" documentaries they show now, that the digits on the display come to a sudden stop when the clapper/loader performs his "mark". There is a good but awkward reason for that : remember that a film camera is nothing but a camera (!!! duh !!!) taking 24 pictures per second. Imagine if each time one of the pictures was taken, the clapperboard decided, just for fun, that now is the time to increment the digits (in reality, there's a 50/50 chance of that happening !!!). You'd film just the adress changes, not the adresses themselves. The adresses, or at least the frames digits, would all be blury. So the clapperboard freezes its digits when the clapper/loader presses the "mark" button, just so that at least one adress can be printed correctly on film.

On the shooting, one (or several) video tape recorder(s) record picture and sound as well as time-code on video tape, on which the editor can immediatly start working. For the wise people reading this, and for the even wiser that just read the pages on the two previous methods : it's just as if, straight off the shooting, we were already at a stage where a video transfer has been performed, and the syncing of sound to that video had been done.

The editor can immediatly start to work on that video copy of the picture, with sound

at the same time-code adresses.

So what happens next ?

|

Picture process |

. |

Sound process |

|||

|

. | ||||

|

|||||

|

the picture of the film is ready at last ! |

|

||||

|

|||||

|